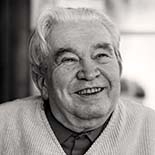

Jaroslav Seifert (September 23, 1901 – January 10, 1986) was a Czech writer, poet and journalist. Seifert was awarded the 1984 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Jaroslav Seifert (September 23, 1901 – January 10, 1986) was a Czech writer, poet and journalist. Seifert was awarded the 1984 Nobel Prize in Literature.

A PLACE OF PILGRIMAGE

Jaroslav Seifert

After a long journey we awoke

in the cathedral’s cloisters, where men slept

on the bare floor.

There were no buses in those days,

only trams and the train,

and on a pilgrimage one went on foot.

We were awakened by bells. They boomed

from square-set towers.

Under their clangour trembled not only the church

but the dew on the stalks

as though somewhere quite close above our heads

elephants were trampling on the clouds

in a morning dance.

A few yards from us the women were dressing.

Thus did I catch a glimpse

for only a second or two

of the nakedness of female bodies

as hands raised skirts above heads.

But at that moment someone clamped

his hand upon my mouth

so that I could not even let out my breath.

And I groped for the wall.

A moment later all were kneeling

before the golden reliquary

hailing each other with their songs.

I sang with them.

But I was hailing something different,

yes and a thousand times,

gripped by first knowledge.

The singing quickly bore my head away

out of the church.

In the Bible the Evangelist Luke

writes in his gospel,

Chapter One, Verse Twenty-six

the following:

And the winged messenger flew in by the window

into the virgin’s chamber

softly as the barn-owl flies by night,

and hovered in the air before the maiden

a foot above the ground,

imperceptibly beating his wings.

He spoke in Hebrew about David’s throne.

She dropped her eyes in surprise

and whispered: Amen

and her nut-brown hair

fell from her forehead onto her prie-dieu.

Now I know how at that fateful moment

women act

to whom an angel has announced nothing.

They first shriek with delight,

then they sob

and mercilessly dig their nails

into man’s flesh.

And as they close their womb

and tense their muscles

a heart in tumult hurls wild words

up to their lips.

I was beginning to get ready for life

and headed wherever

the world was most exciting.

I well recall the rattle of rosaries

at fairground stalls

like rain on a tin roof,

and the girls, as they strolled among the stalls,

nervously clutching their scarves,

liberally cast their sparkling eyes

in all directions,

and their lips launched on the empty air

the flavour of kisses to come.

Life is a hard and agonizing flight

of migratory birds

to regions where you are alone.

And whence there’s no return.

And all that you have left behind,

the pain, the sorrows, all your disappointments

seem easier to bear

than is this loneliness,

where there is no consolation

to bring a little comfort to

your tear-stained soul.

What use to me are those sweet sultanas!

Good thing that at the rifle booth I won

a bright-red paper rose!

I kept it a long time

and still it smelled of carbide.

====

DANCE OF THE GIRLS’ CHEMISES

Jaroslav Seifert

A dozen girls’ chemises

drying on a line,

floral lace at the breast

like rose windows in a Gothic cathedral.

Lord,

shield Thou me from all evil.

A dozen girls’ chemises,

that’s love,

innocent girls’ games on a sunlit lawn,

the thirteenth, a man’s shirt,

that’s marriage,

ending in adultery and a pistol shot.

The wind that’s streaming through the chemises,

that’s love,

our earth embraced by its sweet breezes:

a dozen airy bodies.

Those dozen girls made of light air

are dancing on the green lawn,

gently the wind is modeling their bodies,

breasts, hips, a dimple on the belly there —

open fast, oh my eyes.

Not wishing to disturb their dance

I softly slipped under the chemises’ knees,

and when any of them fell

I greedily inhaled it through my teeth

and bit its breast.

Love,

which we inhale and feed on,

disenchanted,

love that our dreams are keyed on,

love,

that dogs our rise and fall:

nothing

yet the sum of all.

In our all-electric age

nightclubs not christenings are the rage

and love is pumped into our tyres.

My sinful Magdalen, don’t cry:

Romantic love has spent its fires.

Faith, motorbikes, and hope.

=======

LOST PARADISE

Jaroslav Seifert

The Old Jewish Cemetery

is one great bouquet of grey stone

on which time has trodden.

I was drifting among the graves,

thinking of my mother.

She used to read the Bible.

The letters in two columns

welled up before her eyes

like blood from a wound.

The lamp guttered and smoked

and Mother put on her glasses.

At times she had to blow it out

and with her hairpin straighten

the glowing wick.

But when she closed her tired eyes

she dreamed of Paradise

before God had garrisoned it

with armed cherubim.

Often she fell asleep and the Book

slipped from her lap.

I was still young

when I discovered in the Old Testament

those fascinating verses about love

and eagerly searched for

the passages on incest.

Then I did not yet suspect

how much tenderness is hidden in the names

of Old Testament women.

Adah is Ornament and Orpah

is a Hind,

Naamah is the Sweetness

and Nikol is the Little Brook.

Abigail is the Fount of Delight.

But if I recall how helplessly I watched

as they dragged off the Jews,

even the crying children,

I still shudder with horror

and a chill runs down my spine.

Jemima is the Dove and Tamar

the Palm Tree.

Tirzah is Grace

and Zilpah a Dewdrop.

My God, how beautiful this is.

We were living in hell

yet no one dared to strike a weapon

from the murderers’ hands.

As if within our hearts we did not have

a spark of humanity!

The name Jecholiah means

The Lord is Mighty.

And yet their frowning God

gazed over the barbed wire

and did not move a finger —

Delilah is the Delicate, Rachel

the Ewe Lamb,

Deborah the Bee

and Esther the Bright Star.

I’d just returned from the cemetery

when the June evening, with its scents,

rested on the windows.

But from the silent distance now and then

came thunder of a future war.

There is no time without murder.

I almost forgot:

Rhoda is the Rose.

And this flower perhaps is the only thing

that’s left us on earth

from the Paradise that was.