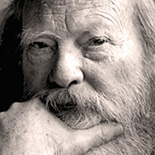

Hayden Carruth (August 3, 1921 – September 29, 2008) was an American poet and literary critic.

Hayden Carruth (August 3, 1921 – September 29, 2008) was an American poet and literary critic.

Carruth wrote more than 30 books of poetry, four books of literary criticism, essays, a novel and two poetry anthologies. He served as editor of Poetry magazine, as poetry editor of Harper’s, and as advisory editor of The Hudson Review 20 years. He was awarded a Bollingen Prize and Guggenheim and the NEA fellowships.

In 1992 he was awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award for his Collected Shorter Poems and in 1996 the National Book Award in poetry for his Scrambled Eggs and Whiskey. Shortly after the debut of Scrambled Eggs and Whiskey, he also won the $50,000 Lannan Literary Award. His later titles include the 2001 collection of poems Doctor Jazz and a 70-minute audio CD of him reading selections from Scrambled Eggs and Whiskey and Collected Shorter Poems. Other awards with which he was honored included the Carl Sandburg Award, the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, the Paterson Poetry Prize, the 1990 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Vermont Governor’s Medal and the Whiting Award.

Noted for the breadth of his linguistic and formal resources, influenced by jazz and the blues, Carruth’s poems are informed by his political radicalism and sense of cultural responsibility.

ASSIGNMENT

Hayden Carruth

“Then write,” she said. “By all means, if that’s

how you feel about it. Write poems.

Write about the recurved arcs of my breasts

joined in an angle at my nipples, how

the upper curve tilts toward the sky and the lower

reverses sharply back into my torso,

write about how my throat rises from the supple

hinge of my collarbones proudly so to speak

with the coin-sized hollow at the center, write

of the perfect arch of my jaw when I hold

my head back — these are the things in which I too

take delight — write how my skin is

fine like a cover of snow but warm and soft and

fitted to me perfectly, write the volupte

of soap frothing in my curling crotch-hair, write

the tight parabola of my vulva that resembles

a braided loop swung from a point,

write the two dapples of light on the backs

of my knees, write my ankles so neatly turning

in their sockets to deploy all the sweet

bones of my feet, write how when I am aroused

I sway like a cobra and make sounds

of sucking with my mouth and brush my nipples

with the tips of my left-hand fingers, and then

write how all this is continually pre-existing in my

thought and how I effect it in myself

by my will, which you are not permitted to understand.

Do this. Do it in pleasure and with

devotion, and don’t worry about time. I won’t

need what you’ve done until you finish.”

=======

THE COWS AT NIGHT

Hayden Carruth

The moon was like a full cup tonight,

too heavy, and sank in the mist

soon after dark, leaving for light

faint stars and the silver leaves

of milkweed beside the road,

gleaming before my car.

Yet I like driving at night

in summer and in Vermont:

the brown road through the mist

of mountain-dark, among farms

so quiet, and the roadside willows

opening out where I saw

the cows. Always a shock

to remember them there, those

great breathings close in the dark.

I stopped, and took my flashlight

to the pasture fence. They turned

to me where they lay, sad

and beautiful faces in the dark,

and I counted them—forty

near and far in the pasture,

turning to me, sad and beautiful

like girls very long ago

who were innocent, and sad

because they were innocent,

and beautiful because they were

sad. I switched off my light.

But I did not want to go,

not yet, nor knew what to do

if I should stay, for how

in that great darkness could I explain

anything, anything at all.

I stood by the fence. And then

very gently it began to rain.

=======

LETTER TO DENISE

Hayden Carruth

Remember when you put on that wig

From the grab bag and then looked at yourself

In the mirror and laughed, and we laughed together?

It was a transformation, glamorous flowing tresses.

Who knows if you might not have liked to wear

That wig permanently, but of course you

Wouldn’t. Remember when you told me how

You meditated, looking at a stone until

You knew the soul of the stone? Inwardly I

Scoffed, being the backwoods pragmatic Yankee

That I was, yet I knew what you meant. I

Called it love. No magic was needed. And we

Loved each other too, not in the way of

Romance but in the way of two poets loving

A stone, and the world that the stone signified.

Remember when we had that argument over

Pee and piss in your poem about the bear?

“Bears don’t pee, they piss,” I said. But you were

Adamant. “My bears pee.” And that was that.

Then you moved away, across the continent,

And sometimes for a year I didn’t see you.

We phoned and wrote, we kept in touch. And then

You moved again, much farther away, I don’t

Know where. No word from you now at all. But

I am faithful, my dear Denise. And I still

Love the stone, and, yes, I know its soul.