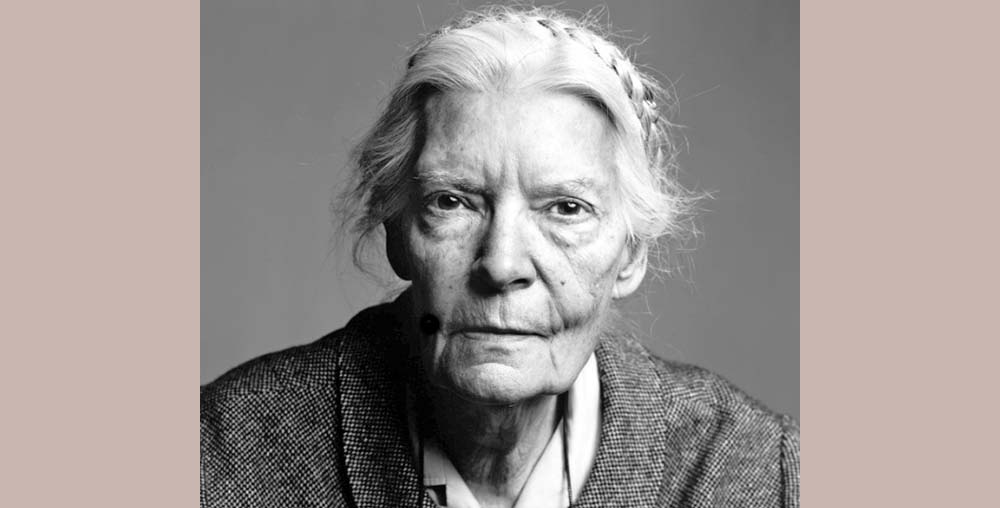

I spent years reading Dorothy’s diaries, articles, letters and books, and poring over videos, recordings and thousands of photographs. I examined every clue I could gather–in my memories, my mother’s memories, the memories of friends, family and strangers. Anyone I could track down, or who tracked me down. Through this process I discovered that I am no different from those for whom even one brief meeting with Dorothy decades ago changed their lives. Through these stories, I have come to believe there is little point in simply admiring Dorothy Day. If you’re going to pay attention to her, your life will be turned on its head.

I spent years reading Dorothy’s diaries, articles, letters and books, and poring over videos, recordings and thousands of photographs. I examined every clue I could gather–in my memories, my mother’s memories, the memories of friends, family and strangers. Anyone I could track down, or who tracked me down. Through this process I discovered that I am no different from those for whom even one brief meeting with Dorothy decades ago changed their lives. Through these stories, I have come to believe there is little point in simply admiring Dorothy Day. If you’re going to pay attention to her, your life will be turned on its head.

After her death in 1980, I sometimes would sit alone in Dorothy’s room in Maryhouse, the Catholic Worker house of hospitality on the Lower East Side, New York, where she lived her last years and where she died. I sat in the armchair where she read The New York Times, The Catholic Worker galleys or the Psalms, a cup of coffee at hand. I wanted to be comforted by her lingering presence, but instead I felt like a swirl of dead and dry leaves blowing about in the wake of her footsteps. I was unable to make any sense of her within my own life, and so I spent years living as if she weren’t my grandmother, where people didn’t know of her, or didn’t know of my relationship to her. But there comes a time when you must return home, even though you aren’t sure you’re ready, for you can’t keep running away, especially from the saint in the family closet.

There is no academic, political, theological or philosophical stance for me to take here.

If Dorothy Day doesn’t rip something open within you, crack wide your heart and leave you with what feels like an affliction, and yet also leaves you breathless with wonder and possibility, then it is all for nothing. All the admiration, accolades, studies, even the canonization process are all for nothing. And I say this not only for myself but for each of us who has been grabbed by her, even if we don’t fully understand why. There is pain, difficulty and an odd exhilaration in allowing and acknowledging Dorothy into your life. It will lead you down a path you have little control over, if you are true to it.

When Dorothy died people wondered if the Catholic Worker movement would survive her passing. The CW is celebrating its ninetieth anniversary this year–I think that question can be laid to rest. A better question to ask now is: What is she still teaching us? I have–daringly–identified nine major teachings, which I have referred to as consolations, lamentations or ruminations, but but most commonly “provocations.” These are not rules or step-by-step instructions. They are more akin to adding ingredients to a soup, or a weaving of intertwining threads, and I may be doing a disservice by putting them in some kind of order.

I can’t claim to know much about each provocation, and I have many more questions than answers. Dorothy spoke of the mystery of our freedom–one of the greatest gifts God gave us, she said. She also said that we struggle against both freedom and responsibility, and we always will. There is no point in telling people what to do. It has to be a revolution from within, a revolution of the heart. I do see the provocations as an alternative to anger, lethargy, despair, helplessness, or worst of all, indifference. They are a practice and a map to a path you must forge for yourself. As Bilbo said (and I’m comfortable quoting Tolkien because my grandmother and I read The Hobbit together the summer of 1973): “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door. You step on to the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

But how do you take that first step? I think desire, however vague, and a deep sense of personal responsibility is the best way to begin. One of the provocative choices Dorothy presents is: Do we declare we know exactly who she was? Or do we accept her challenge and just “do the work”? Dorothy infamously said, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” Many have worried like a dog with a bone at this, wondering what it says about her. But of course it isn’t about her–it’s about us. And this fits nicely with the first provocation–make yourself deeply uncomfortable.

-1-

Make Yourself Deeply Uncomfortable

Dorothy’s life, her work and words can be utterly uncomfortable. Pick any element of the Catholic Worker program and philosophy, and you might find yourself running for the hills. Opening houses of hospitality in which nothing is asked of those who are given refuge, whether the “deserving” or “undeserving” poor. Her stance on nonviolence can provoke people into anger, and her insistence on voluntary poverty cuts at the very roots of our society and most of what we strive for. She was an “obedient daughter of the Church” and yet challenged and chastised the bishops when she saw need. She insisted on always responding to the here and now in practical terms, emphasizing personal responsibility and not resting in ideology. All the Catholic Worker beliefs are expressions of the deep trust in the Gospels, a deep trust in Christ against all reason. Such trust can be deeply unsettling and uncomfortable.

Dorothy rarely felt comfortable. She felt keenly the pressure of the drunkenness, the madness, the anger of those who came to the Worker, along with the never-ending struggle of living with the noise, filth and smells. She wasn’t a natural public speaker, she could find people’s neediness, and criticism, overwhelming, and she needed her solitude. It never became easy for her, and yet she continued. There are no bromides to be found here, no cheap grace, no sentimentality, no soothing or sensible solutions. And yet, paradoxically, all of these Catholic Worker elements also have such capacity toe lead to joy.

Making ourselves deeply uncomfortable requires an honest self-examination of how we are choosing to live our lives, but there can be debilitating discomfort in feeling we have done far too little or made too many mistakes. Or that we are part of the problem, and not the solution, or maybe both. And what value lies in lingering feelings of deep regret and shame? Sometimes it is difficult to recognize the difference between such powerful emotions as grief and discomfort. Or of knowing the difference between which discomforts are meaningless and which aren’t. We do need to feel compassion for ourselves, rest when we can and find our spiritual sustenance, but still we can’t stop there. It was often said of Dorothy that she afflicted the comfortable and comforted the afflicted. I think she asks us to do this within ourselves, holding oneself to discomfort while generously giving comfort to others. It takes courage to make yourself deeply uncomfortable, and it is a form of intentional suffering. Truth can be extremely uncomfortable, both in speaking it and hearing it. Then there’s that discomforting shock when you realize that something you were unequivocally sure of is just plain wrong. Probably the most difficult aspect of this is sometimes there is no solution, or no sensible solution, to what discomforts you, There is no point in feeling comfortable with Dorothy, and yet we need comfort of some sort, and that, paradoxically, may lie within the discomfort.

I have found both in being Dorothy’s granddaughter. I am comforted by my Dorothy stories and by the memory of our love for each other. For years I found comfort in the relics I held on to–her last driver’s license, the Hopi woven man in a maze she used to have in her room, and the woven Bolivian bag she used during her last arrest in California in 1973, picketing with the farmworkers at the age of 75. l thought these relics would ground me in some way, slake a thirst for some mysterious element of hers. I have been letting these relics go one by one over the years, passing them along to others, as I don’t feel the need for that comfort any more. As Dorothy’s granddaughter, I’ve been made to feel intensely uncomfortable, beginning when I was barely out of my teens and an old friend of the Catholic Worker asked me, “Are you going to follow your grandmother’s footsteps?” And before I could stop myself, I said, “Hell, no.” He was shocked, and replied, “You should be ashamed of yourself, you, Dorothy’s granddaughter.” I still stand by my statement, and I insist on forging my own path, but of course I did feel ashamed. And uncomfortable. I’ve been uncomfortable all my life being her granddaughter and will always be so. l have, though, made my peace with this, and I carry on as best as I can. Just as Dorothy did.

-2-

Follow Your Conscience

In the history of the Catholic Worker, the question of following one’s conscience was most agonizingly examined when young men came to Dorothy asking if they should go to war. She had no easy answers. “Follow your conscience,” she replied. She added that it’s good to have a well-informed conscience, but follow it even if it isn’t. This could be a a life-and-death decision even if one became a conscientious objector. You must be prepared, she said, to sacrifice just as much as the soldier does.

One of the most difficult, lonely and personally dangerous times for Dorothy was when she followed her conscience during the Second World War, when very few supported her, many were actively hostile, and the Catholic Worker lost the majority of its readers. Following one’s conscience can seem utterly useless, but as Dorothy said: “We can throw our pebble in the pond and be confident that its ever widening circle will reach around the world.” Dorothy forged a path of such complexity, this embrace of Catholic Church teachings and the primacy of the conscience, that many just don’t know what to make of it. How far would Dorothy’s faith have led her if he hadn’t been able to find a way to express this? She believed following one’s conscience is acting on one’s faith. Her relationship with the Archdiocese of New York was cordial but uneasy, and she was called to the Chancery to respond to complaints (after which she often visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art). But she had such inner authority of knowing she was following the Gospels that she believed any trouble would sort itself out. (She did say during the 1960s that it’s best to dress ordinarily when doing extraordinary things, for example, looking like a suburban grandmother while being arrested for civil disobedience against nuclear weapons.)

Dorothy found great freedom within the Church to follow her conscience, even with the Church’s uneasiness, but my mother, Dorothy’s daughter Tamar, did not. For her, leaving the Church was a refusal to live in opposition to her conscience, and it came at a great price. Some of Tamar’s last words as she lay dying were, “I lost my faith. ” I don’t know what it was she longed for, so full of regret, but I could not help but feel the unworkable tension between some church teachings and her conscience. What a peculiar and mysterious thing–this still, small voice within. Where does it come from? And how do you know it? How do you strengthen it?

I think that perhaps we can begin by letting go of protecting oneself, whether individually of institutionally. By trusting in the innate sense of good within ourselves, in our own judgement and courage. By developing good judgement so we are less likely to fool ourselves into believing we are following our conscience when we are following our ego or fear. By building up courage–you don’t know how your family or community will respond, and yet there is every chance it may be in wonderful ways. And by being careful of relinquishing all responsibility to others–to laws, strictures, societal pressures, or mob thinking. Conventional wisdom can be spectacularly wrong and is rarely able to answer the most vexing of human problems. I think of conscience as a muscle–the less you use it, the weaker it is. Start with a small load, and maybe this will be all that we can do. Maybe it doesn’t have to be a loud act at all. We have endless opportunities to follow our conscience; there just needs to be a willingness. When you do it, you will know the feeling of it. When you don’t do it, you won’t be able to forget it. Your conscience will keep coming back, no matter how repressed, denied or starved.

There is such utter power and yet utter vulnerability in the one who takes a conscientious stance. It’s hard to forget Franz Jagerstatter or Martin Luther King Jr, and it’s easy to feel following one’s conscience is not for us mere mortals. But I don’t think it’s possible to create a life where you are never confronted with your conscience. There’s a feeling of homecoming, a sense of one’s true self, and an inherent joy and breathless wonder in this. Could this be true–that I have within me a sense of conscience that retains its integrity, no matter what?

Dorothy believed that we can never lose that sense, and with a bit of encouragement, a mall step toward it, it will leap in gladness towards you.

-3-

Find Your Vocation

Dorothy said: “You will know your vocation by the joy it brings you.” She added that it would be good if your work can be in the context of the Work of Mercy, but the essential thing is joy. Dorothy’s vocation was a a writer, which she began in childhood, writing short stories on a Lake Michigan pier with her sister, and ended nine day before her death at Maryhouse in NYC. Her writing was evocative, detailed, with an eye for the unusual and beautiful, and fueled by constant curiosity. In all the years of the Catholic Worker, very few people other than Dorothy have been able to capture that elusive beauty, that wild improbability of joy and love amid tragedy, illness, destitution and death that is the movement’s story.

“Work is so necessary and so healing,” my mother said to me when I was young and searching for my place in the world. “Find your vocation–what you are good at.”

How do you live a life in which you aren’t divided against yourself, where your work is an expression of the best of yourself? The artist Robert Henri said that we are not here to do what has already been done. He also said that art is a matter of doing things, anything, well. This is no light matter, and few have the courage and stamina. If you succeed, even in some small measure, you may have to sacrifice for it, as well as take delight in it, all your life. I think this could be said of all those who live authentic vocations.

I think with a true vocation every aspect of your life is involved. We are shaped by our work-physically, emotionally and spiritually. It is how you live in the world, and this is nothing to be careless about The beauty of individual callings is that they can be found in any kind of work, but there does need to be some sort of reckoning with the common good. I can’t see it being possible to feel joy doing something that your conscience tells you is wrong. In the 1980s, when Joseph Campbell was broadcasting his advice, “Follow your bliss,” my mother cried out, “Yes!” But what a societal backlash followed. You can’t do that–you can’t follow your bliss. Who would do all the real work, then?

For many, recognizing and being able to follow one’s vocation is no easy task. It can be a provocation to oneself and to one’s family, community and society. There can also be a confusion between vocation and career, and you may need to separate your vocation from earning money.

There are many ways we kill our own calling and the calling of others. Be realistic, don’t be selfish, how are you going to pay the bills? You owe it to your family. Aren’t you fiddling while Rome burns? Your parents didn’t get to do this–what makes you worthy?

But what right do we have to crush someone else’s dream, or even our own? Sometimes your vocation is deliberately, actively kept from you, usually for reasons that are dehumanizing. What to do then? Maybe choose your battles, your priorities. Be creative, or be a warrior. If it doesn’t change for you, it may change for someone else coming after you. Maybe seeing the joy in another’s face as they do their work can allow us the generosity to see it within ourselves. Following one’s vocation is an act of generosity in and of itself, and it will be contagious. What a wonderful gift to give, this joy in one’s own work, this inner power of living a fulfilling life. We either believe each of us, no matter what color, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic bracket or abilities, has a vocation, or we don’t.

What a powerful act to look around at individuals, whether you know them or not, and believe that they each have a calling. What a way to instantly change one’s perception of a person. How then can you not be affected by the injustices of others not being able to pursue their calling? Isn”t it then our obligation to do what we are called to do? Our calling may require us to live with an awareness of the gaping difference between what we imagine we can do and what we can actually do, but if you deny your vocation, like your conscience, it will keep returning, no matter how many years pass. And once you accept it, you will feel like an arrow sent on its way with no turning back. And it will be part of the Works of Mercy.

-4-

Face Your Fears

During the turmoil of the 1960s, Dorothy once said: “I know what human fear is, and how often it keeps us from following our conscience.” She spoke of many kinds of fear–of losing material.goods, of poverty, and “there is the strange business of bodily fear” which she experienced when she was shot at while visiting the integrated community of Koinonia, Georgia, during the civil rights movement.

Dorothy bad a penetrating gaze, unnervingly direct and unsettling. Her daughter Tamar, my mother, referred to it as “the Look,” which she had, too. I can still feel this Look from two women who knew much of the human condition, yet kept their fierce and loving eye on it. I can try to be no less courageous and honest than they, but if I’m not careful, this discussion of fear could be a long one.

There is fear of speaking the truth; of not being enough; of other people’s neediness; of one’s own conscience or vocation; of commitment and of sacrifice. There is fear of making a fool of yourself, and what is that but fear of revealing your deepest self only to have people attack or ridicule it? In response to this, Dorothy said, so be it–we are fools. And there are those who live in a constant, indescribable fear for their own lives or the lives of their families and communities. I can’t speak for this fear. But there is one fear I feel compelled to write of above all others–fear for the Earth and her creatures. I can’t help but wish deeply that science and religion would come together to face this most dire fear. We now all live, I am sure, whether admitted or not, with a deep hum of anxiety and fear. And of sadness.

My mother quoted often to me from Liberty Hyde Bailey, horticulturist and author of The Holy Earth, published more than one hundred years ago, in which he called for a spiritual relationship with the land and cooperation rather than dominion. He said: “Of all the disturbing living factors, man is the greatest.” It isn’t easy to see all land as holy. It is hard for me to see Staten Island as sacred, where Dorothy began her conversion, Tamar was conceived and where both were baptized. It has been abused for decades, including containing at one point the world’s largest man-made structure, the Staten Island dump. But Dorothy had an extraordinary sense of the earth’s beauty. She had an instinctive awareness of what the Irish philosopher John Moriarty meant when he said the land never loses its integrity. “We need a reverence for the earth,” Dorothy wrote. “I took my grandchildren one day out.. and said, “Come on out and let’s kiss the earth.” “What if we all, biologists and theologians included, get up from our tasks, from our pew and research labs, desks and assembly lines, and run outside as if the very devil were at our heels, to kiss the earth? Why is it so hard to express love for the ground we stand on, this giant globe pulsing with mycelium and lava, microbes and all manner of beings? Is it because we have so thoroughly bought into the notion of dominion that to bend ourselves to the earth is an impossibility? Or is it because the fear of its loss is unbearable?

How I wish that we all look about at our landscape and feel such love and beauty that we will do whatever is in our power to protect it and to help it be what it longs to be in every particle of its being. To see the earth glow and sparkle with creation and feel full of love for it, even as we may be overwhelmed by fear for its destruction. Can we allow ourselves to grieve for what we are losing and yet not be afraid? Can we find the courage to do what needs to be done?

Let’s give courage to one another. Let’s be curious and not afraid. Dorothy said that we need to trust Christ when he tells us to not be afraid. Seamus Heaney and his wife, Marie, often visited Connemara in Ireland where my husband and I lived for years, and occasionally we would see them walking down the streets of Clifden. While I never spoke to him, I felt that moment of grace we receive from a person who sees the world as it is and yet still loves it dearly; perhaps even more so, the Look of a poet. The last words Seamus Heaney texted to his wife before he died, were Noli timere–Be not afraid.

-5-

Fail Gloriously

“I feel like an utter failure,” Dorothy wrote when she was seventy-nine, forty-five years after that day of, May 1, 1933 when she and several others walked to Union Square in New York and began selling The Catholic Worker paper for a penny a copy.

“The older I get the more I feel that faithfulness and perseverance are the greatest virtues–accepting the sense of failure we all must have in our work, in the work of others around us, since Christ was the world’s greatest failure.” But she also said, “Christ understands us when we fail.” I can’t forget or explain her sense of personal failure, and I can’t say I know what she meant.

I don’t know what failures she felt most heavily, whether it was in her work or as a mother and grandmother, but whatever its source, it is painful to hear. We can’t deny this even in the face of her possible canonization. We must always expect failure, Dorothy warns us, and when she speaks of her failures, mine seem wretched and inconsequential. I need a worthy failure, to fail gloriously at those things that are worth failing at, and even in the failure continue to persevere. To fail at doing what I am called to do and yet still answer this call.

“When you open your heart, you open it to suffering.” I imagine saying to my grandmother. “Of course,” she would say, “and to the failure of the Cross. Suffering and failure are inevitable.” I am feeling that look, that Grandmother look, that gaze of clear-eyed honesty, strength, understanding, compassion, perception and love for a world given even at the cost of one’s own prosperity. Even in the face of failure. But I think there is power and freedom in expecting and accepting failure, in knowing the improbability of success in a venture and knowing you need to do it anyway. Maybe a better definition of success is knowing you did your utmost best. “In the meantime, you’ve got to live,” Dorothy’s daughter, Tamar, cried when she was a young mother of four and facing her failures, but still impatient with all the dire, eleventh-hour predictions that flooded the world in the aftermath of the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Failure is mysterious. Things that at the moment feel catastrophic may lead to something else, though we may not live to see this.

Something having failed to work may develop into something that will work. St Francis said to start by doing what’s necessary, then what’s possible, and suddenly you are doing the impossible. The choice given to us through our failures is how to move forward. We must keep going, we must continue regardless with faithfulness and perseverance, for who are we to judge what is failure and what is success? I thought it was that moment in my mother’s final hours when she said, “I lost my faith” that wouldn’t let me go, but she also said, ”I failed the children,” and for this, too, I wept. What did she want for her children that she fell she hadn’t been able to give? Our contentment through fulfilled lives? An element of faith? Her words, “I lost my faith,” were easier to hear at the time, but now I feel a connection between the two. Tamar knew what a life of faith could achieve. That it could shape reality. She had seen this, after all, in her mother’s life and in the Catholic Worker regardless of Dorothy’s feelings of failure. Aren’t we obligated to see and admit our failures? Have we become habituated to them, particularly those on a colossal, unimaginable scale? Are some failures just insupportable such a our failure in our responsibilities to each other, to the Earth, to the wild? How do we live with these failure and continue on? Continue, Dorothy would say, with acts that have every possibility, probability, certainty of failing in any sensible manner, but you do it anyway. Poets, therapists, theologians, artists, and political leaders often have something to say about failure, but after a lifetime of following her conscience and her calling, Dorothy Day just comes out and says it, “I feel like an utter failure.” Yes, I say. But let’s fail gloriously rather than wretchedly.

-6-

Embrace Beauty

In her last years, Dorothy often woke up hearing in her mind Dostoevsky’s quote, “The world will be saved by beauty.” This spoke to me faster than anything else he said, though I don’t entirely know why. Claiming a definition of beauty is impossible; we can only make stabs at it. But this I know–we must open ourselves up to beauty. And we will know it in a moment of mysterious recognition, and it will transform us. No matter how bleak a slum Dorothy lived in and how dire the circumstances, to her the world always gave the gift of beauty and its potential even in what seems full of suffering or tragedy, or transient and fragile. Her daughter Tamar had a gift of seeing beauty in the tangle and disorder of nature. Weeds, she said, grow long roots and bring nutrients to the top. They feed and give shelter to the creatures though her neighbors did not appreciate her accommodation of weeds, or the way they provided protection for her resident skunk. When beauty suffuses you, it is love that has your total attention. What else is beauty but the language and love of God? And the laughter of the Earth, the laughter of Creation. It is delight itself. I am saved by beauty every single day, without fail. There is no breaking of that covenant, and it is so faithful that it’s easy to become blind to it or take it for granted or deny its value. Beauty is God’s gift to everyone, even the thrush singing contentedly as the sun sets, without condition. This love, desire, and praise for beauty is my working definition of my religious and spiritual impulse. Often it seems we are at war with beauty, destroying it systematically and casually except when it can be used as a commodity. And then, within one generation, we no longer know what good soil is, what the forests used to be, or what the night sky look like without the glow of electricity. Environmental degradation is usually called progress; Dorothy called it a form of poverty. Opening up to beauty isn’t easy; it isn’t mere sentimentality. “Quiet your heart.” says St Teresa of Avila, “so God can find a place to rest.”

Here on the Beara Peninsula. on the southwest coast of Ireland, I live in such beauty while so many others lead troubled and rage-filled lives. Because of this gift of beauty I wish to speak, as foolish of a gesture as this may be, for the curlew and the corncrake who struggle to raise their young, and the small patches of scrub land being bulldozed over as I write. These are small beings unattended to in this great wide world, each giving the gift of beauty. But it isn’t easy to witness the suffering of even the smallest of creatures. It isn’t easy to quiet my heart. Do I yet know why, when my thoughts turn to God, I turn them to the moon and stars and wind, which seem so pure and untouchable in their beauty? What beauty resides in the wind blowing through the hawthorn and sycamore, the night rain sparkling in flowering gorse, the sun rising above the Miskish Mountains. Yes! Yes! I say to it all. How glorious. I live a life of kings and queens, moguls and popes–no, greater than they. They should envy me. These are moments of this mysterious transformation. This is the power of beauty.

I am called to perceive beauty with every atom of my being, to be irrevocably changed by it, and, yes, to weep at its destruction. To not turn away saying that this is too much, and I can’t help. To allow it to open up my heart, even though I can see and feel the loss already, and I am afraid. What choice do I have? Shall I linger in this world pretending to be otherwise engaged? Will I do nothing? A blackbird sings on a wire while the pines whisper iove songs to the ravens, and the swallows swoop in and out of the shed-all masters of contentment. in this patch of being, all is good, and all manner of things are good. We are cradled by beauty which saves us every day. Oh, how I would love to have beauty drip from my fingertips as easily as exhaling, to fling it about riotously and have it fall as gracefully as the sunlight on my lap.

-7-

Laugh

Big Dan Orr was a member of the Catholic Worker family who showed up at the door when he had lost his job as a driver during the Great Depression. He sold the Catholic Worker on a street corner in Union Square, and when he saw Dorothy approaching, he’d shout, “Buy the Catholic Worker! Romance on every page!” Stanley Visniewski, who arrived at the Worker as a seventeen year old and ended up staying his entire life, used humor to lift everyone’s spirits, including his own. He liked to say in his Brooklyn accent, “Here at the Catholic Worker, we don’t have a single cockroach. They are all married with children.” Stanley often began his jokes with the phrase “Here at the Catholic Worker … ” Here at the Catholic Worker, we change our sheets every day–we move them from one bed to the next.” “Here at the Catholic Worker, we always have an available bed–if you don’t mind sleeping thirteen to a bed.”

My favorite Catholic Worker story is the one of Lena and Mother Teresa. Lena lived in the foyer of Maryhouse in the winter when it was too cold to live in her usual spot on a corner of Union Square. She would refuse a room and preferred to stay on a bench from where she would ask anyone who walked past her, “Got a cigarette?” She even asked Mother Teresa when she came to visit. “No, I’m sorry, I don’t,” Mother Teresa replied. To which Lena said the same thing she said to everyone who didn’t have a cigarette, “Well, then, what good are you?”

Both Dorothy and Tamar, my mother, had a similar laugh–a high-pitched joyous giggle. I think there are two things that they found humor in–the absurdity of the human condition and the joy of it. Dorothy still laughed like a young woman even in her eighties, and in recordings you can hear that laughter, particularly when serious young people would ask her questions about such things as spiritual discipline and maturity. She would laugh and sigh as she often did when faced with seemingly intractable problems before shaking her head and saying, “I don’t know.”

Dorothy’s humor is in danger of being lost with those fierce and stern photos that people often seem to prefer. This irritated my mother no end. “Dorothy saw the humor in so much, and there was so much warmth in it. She could warm people up just by walking into a room,” Tamar said. Many people also delighted in Tamar’s laughter and in the authenticity of it. Spontaneous and unexpected, it was laughter in the face of hardship.

Dorothy often quoted John Ruskin about the “duty of delight.” She was reminded of this while coming across it visiting Vermont in the early 1960s, when Tamar’s marriage had fallen apart, she was a single mother of nine and in the slow, painful process of leaving the Church. Tamar had her own take on this. “The worse your disaster, the more you laugh,” she would say.

I miss my mother’s laughter and her eyes lighting up with delight. I miss the days I would make her blueberry pancakes and cups of tea, and we would sit around the kitchen table, and eat and talk, and laugh. There is an inherent loving kindness in humor that is gentle and self-aware. It is a great expression of hope. It provides distance so you can observe things more accurately and have more self-understanding. Humor helps you to become an observer of yourself. It is self-deprecating and defuses the ego. It’s good for your health, it helps make you more resilient, and it’s a great way to connect with others. As Stanley Visniewski well knew, wielded with sensitivity even corny humor helps deescalate tense situations. It brings delight in the absurdities of life. It helps us to see the good in the world. It’s an antidote to despair and anxiety. We need laughter. We just can’t lake ourselves too seriously.

Once, when I was taking things far too seriously, I asked my husband what he thought ”holiness” meant “Holiness,” he says, “is being faithful to your true self. There is no difference between your inner and outer life.” He then adds, “Well, that’s what I believe today. Ask me again tomorrow.” So I ask him the next day, and, imitating his mother’s north London accent, he says, “Oliness is wot needs mending.”

-8-

Love

A Dostoevsky quote that Dorothy liked to repeat was, “Love is a harsh and dreadful thing compared to the love in dreams.” She also aid there is nothing else worth writing about, and so much of her writings is on the meaning of love, the practice of love, the work of love. ‘The world will be saved by beauty, and what is more beautiful than love?” she said. There is such a miracle and such improbability in love.

Love and create community, Dorothy said. Don’t do it alone. Not that it’s easy. Community is sword grass in the hand, she also said. Yet we can only form community in a damaged world–we are the damaged world. Destructive forces are attracted to this striving towards community. Every Catholic Worker house will have experienced that one person who comes with seemingly nothing but sheer destruction on their mind. Love may be the only thing strong enough to withstand the strain. I understand now why Dorothy was drawn to the little way of St Therese of Lisieux even as she had created the behemoth of the Catholic Worker. “I always learn the hard way,” she said. “But is there any other?”

When I think of community, I think of forests and of mother trees. This may be because I come from a land that is all trees, Vermont, and I now live in Ireland, a country that is a scant one per cent deciduous forest. A forest is a system of cooperation, adaptation and resilience. Its underground web of roots and mycorrhizal fungi is a massive network through which trees feed one another, often cross-species. Mother trees nurture hundreds of saplings by sending them carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus. water and hormones. If loggers take out too many mother trees, the whole forest system collapses. Leave in enough and the forest has an enormous capacity to heal. If the forest floor can do this, surely we can?

This talk of mother tree brings me, of course, to my mother, Tamar. The grief at losing someone you love can unmoor you. In the last year of my mother’s life, my fear of losing her kept me from seeing her too clearly as she sat in her wheelchair planting basil with fingers that could no longer feel. Maybe I was afraid that if my gaze lingered too long on the soft, sunken curve of her cheeks, I wouldn’t be able to bear her departure. Now, I want to be with my mother’s voice and with that sparkle and laughter. I want to touch that cheek softened by time. I want to fee1 her love. It is said that love, which for me is the basis of my religious impulse–with beauty, and probably most of my other impulses is a matter of hardwiring in the brain, as is understanding metaphors, and this hardwiring can be blocked or damaged. I could lose my ability to love or to read poetry from a bad car accident. Now that is precarity.

Love often feels so distant from us that we can scarce understand it, recognize it, or believe it. Love is the measure by which we shall be judged, but we ourselves have no direct way of measuring this. We only have the giving and receiving of it–acts of kindness, attention, time, comfort, any gift at all. We all have experiences of love and community. Find community, share meals with others, and explain the hope that is in you.

Dorothy said, If you are going to accept this awareness of love, nothing but the best endeavors will do: serving soup and coffee, handing out clothes, providing showers, talking, writing, and leaving behind such a compelling vision that the Catholic Worker movement continues ninety years later. This is the Church that Tamar never left–a faith bursting with the living breathing God felt through the heart and the down-to-earth practicality of having a table and chair for a hungry, cold, lonely and despairing person to sit at with a cup of coffee, bread and soup, and companionship. When Dorothy opened the door, it wasn’t only to the destitute. Every person who walked in was searching for something, and they are still coming to the door searching. And in this flow of individuals, in this love in action, Dorothy saw the face of God.

– 9-

Pray Abundantly

Dorothy’s diary entries in her final years were like drops of distilled prayer. Frustrated with not being able to attend a protest against nuclear war, she wrote, “My heart ‘went back on me’ and a deplorable state of weakness kept me on the beach. Where I can at least pray. ‘At least’! What an expression! Hard work, praying, and trying to subdue a rebellious spirit.” She later wrote, “If I did not believe profoundly in the primacy of the spiritµal, the importance of prayer, these would be hard days for me, inactive as I am.”

And as she came closer to her end, she wrote, ”My job is prayer. Sometimes I feel it is like a prayer wheel, mechanical.” Dorothy had a wide definition of prayer. She believed that writing, music, art and reading could all, be forms of prayer. She also believed in importunity and perseverance in asking God for what you want. Not for what you need, she said. Everyone should be able to get what they want, a statement that frightened some, for who knows what havoc could be wreaked if people got what they wanted.

She had no such worries. Pray extravagantly–don’t be timid, don’t be parsimonious. Pray abundantly and in any way you can. I have three major impediments to prayer–I either believe I don’t know how to pray, or I believe I do, or I pretend to be otherwise engaged. I more often than not send my prayers out to the creatures such as the swallows who travel from the Beara Peninsula to South Africa and back again. Many of these prayers are heavy with love and fear and are in the form of begging for forgiveness. I apologize to everything–animals, plants, trees, the wind, the water. I can’t separate sorrow and guilt from my prayers, the most common one being, “St Francis, please have mercy,” usually for a creature that is already dead or a tree that has been cut down, but as my grandmother liked to repeat, there is no time with God. Sometimes, though, I just want to complain. Praise, love, gratitude on good days; lamentation and grievance on the bad.

When asked if I believe my grandmother is a saint, I reply, yes, I do, and I say that I pray to her. I currently have a prayer written on a small blue sticky note I placed under a statue of St Joseph: “Dear Granny, Please bring to us the derelict red terraced house next to the paper shop, the one with the statue of the Blessed Mother in the window. I want to create an art studio of hospitality.” Let’s see what she makes of that. I often find myself thinking of Dorothy’s connection to the sea. I live near the sea, and, as she did, I find deep spiritual sustenance from it. What prayers exist in the turning wheel of each tide! This fierce, unimaginable force continues to drip beauty from its fingertips and to care for its beings, day after day after day.

This is then the deepest joy–sunlight on my hand, the call of the curlew, my love next to me. There is love here of the best kind. I hold my palms open–it seems easier this way. I hold my heart open–I can do no less. Which is it–the inhale or the exhale that fills me with You? The goal is to rest gently, even for a moment in the arms of all that is wondrous in this world. To be awake and brave and filled with gratitude even in the darkest times. To lay myself, scoured by life, before hope, faith, and love, for these are not useless gestures and with them we can skew any data we believe we rely on. And then to say in prayer: Here I am.

I cannot tell if these filaments of prayer are as solid as my hand or as ephemeral as the air my hand holds. I cannot tell if they are not only cupped in my hands but are flesh itself, the holder and the held. I can only try day after day to say a prayer for the moment when I open my chest as if I were opening a coat, and say: “Look, look. Here I am, your small Kate, one iota of a wave lapping against the shores of Coulagh Bay. Here is my quiet heart for You to rest in. Here is my love of the Earth, here is my unassailable belief in the sacramentality of all, this holiness of being. Here it all is for You.”

— © The Catholic Worker, October-November 2023, by Kate Hennessy