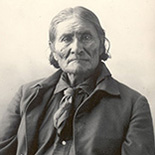

Heȟáka Sápa (Black Elk) (December 1, 1863 – August 19, 1950) was a famous wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine man and holy man) of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux). He was Heyoka and a second cousin of Crazy Horse.

Heȟáka Sápa (Black Elk) (December 1, 1863 – August 19, 1950) was a famous wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine man and holy man) of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux). He was Heyoka and a second cousin of Crazy Horse.

When Black Elk was nine years old, he was suddenly taken ill and left prone and unresponsive for several days. During this time he had a great vision in which he was visited by the Thunder Beings (Wakinyan), and taken to the Grandfathers — spiritual representatives of the six sacred directions: west, east, north, south, above, and below. These “…spirits were represented as kind and loving, full of years and wisdom, like revered human grandfathers.” When he was seventeen, Black Elk told a medicine man, Black Road, about the vision in detail. Black Road and the other medicine men of the village were “astonished by the greatness of the vision”

Black Elk had learned many things in his vision to help heal his people. He had come from a line long of medicine men and healers in his family; his father was a medicine man as were his paternal uncles. Late in his life as an elder, he related to John Neihardt the vision that occurred to him in which among other things he saw a great tree that symbolized the life of the earth and all people. Neihardt recorded all of it in minute detail, and consequently it is preserved in various books today.

In his vision, Black Elk is taken to the center of the earth, and to the central mountain of the world. What mythologist Joseph Campbell explained as “the axis mundi, the central point, the pole around which all revolves…the point where stillness and movement are together…” Black Elk was residing at the axis of the six sacred directions. Campbell viewed Black Elk’s statement as key to understanding myth and symbols.

And while I stood there I saw more than I can tell and understood more than I saw; for I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being. And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy.

Black Elk was involved in several battles with the U.S. cavalry. He participated, at about the age of twelve, in the Battle of Little Big Horn of 1876, known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass to the Lakota; and was injured in the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.

In 1887, Black Elk traveled to England with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, an experience he described in chapter twenty of Black Elk Speaks . On May 11, 1887, the troop put on a command performance for Queen Victoria, whom they called “Grandmother England.” He also described being in the crowd at her Golden Jubilee.

Black Elk saw similarities between Christianity and the Lakota religion which allowed him to practice as a medicine man while also being Catholic. Black Elk was a leader in the revival of the Sun Dance (an important religious ceremony among several tribes) and its reinstatement in Lakota life. Lakota traditionalists now follow his version of the dance.

Since the 1970s the book Black Elk Speaks has become an important source for studying Native spirituality, sparking a renewal of interest in Native religions. Black Elk worked with John Neihardt to give a first-hand account of his experiences and that of the Lakota people. His son Ben would translate Black Elk’s stories, which were then recorded by Neihardt’s daughter Emid, who would then put them in chronological order for Neihardt’s use.

Black Elk married his first wife, Katie War Bonnet, in 1892. She became a Catholic, and all three of their children were baptized as Catholic. After her death in 1903, he became a Catholic in 1904, when he was christened with the name of Nicholas and later served as a catechist. He continued to serve as a spiritual leader among his people, seeing no contradiction in embracing what he found valid in both his tribal traditions concerning Wakan Tanka and those of Christianity. He remarried in 1905 to Anna Brings White, a widow with two daughters. Together they had three more children and remained together until her death in 1941.

Toward the end of his life, Black Elk revealed the story of his life, and a number of sacred Sioux rituals to John Neihardt and Joseph Epes Brown for publication, and his accounts have won wide interest and acclaim.

Black Elk’s Prayer: Neihardt wrote the prayer shortly after the 1931 historic talks he had with Black Elk at Pine Ridge Reservation. He was able to capture in poetic form what the great Sioux holy man was relating to him in Lakota conversation. In 1971 Neihardt recorded his recitation of the prayer. Thirty five years later, grandson Robin composed the music and combined it digitally with John Neihardt’s recording. The old photos in the video clip were taken by John Neihardt and his daughter Hilda during the 1931 meetings.