The daguerreotype process, or daguerreotypy, was the first publicly announced photographic process, and for nearly twenty years, it was the one most commonly used. It was invented by Louis-Jaques-Mandé Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839. By 1860, new processes which were less expensive and produced more easily viewed images had almost completely replaced it. During the past few decades, there has been a small-scale revival of daguerreotypy among photographers interested in making artistic use of early photographic processes.

The daguerreotype process, or daguerreotypy, was the first publicly announced photographic process, and for nearly twenty years, it was the one most commonly used. It was invented by Louis-Jaques-Mandé Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839. By 1860, new processes which were less expensive and produced more easily viewed images had almost completely replaced it. During the past few decades, there has been a small-scale revival of daguerreotypy among photographers interested in making artistic use of early photographic processes.

To make a daguerreotype, the daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish; treated it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive; exposed it in a camera for as long as was judged to be necessary, which could be as little as a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or much longer with less intense lighting; made the resulting latent image on it visible by fuming it with mercury vapor; removed its sensitivity to light by liquid chemical treatment; rinsed and dried it; then sealed the easily marred result behind glass in a protective enclosure.

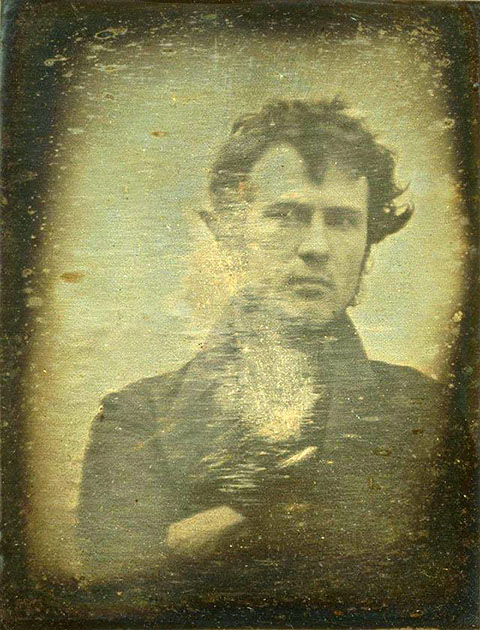

Viewing a daguerreotype is unlike looking at any other type of photograph. The image does not sit on the surface of the metal, but appears to be floating in space, and the illusion of reality, especially with examples that are sharp and well exposed is unique to the process.

The image is on a mirror-like silver surface, normally kept under glass, and will appear either positive or negative, depending on the angle at which it is viewed, how it is lit and whether a light or dark background is being reflected in the metal. The darkest areas of the image are simply bare silver; lighter areas have a microscopically fine light-scattering texture. The surface is very delicate, and even the lightest wiping can permanently scuff it. Some tarnish around the edges is normal, and any treatment to remove it should be done only by a specialized restorer.

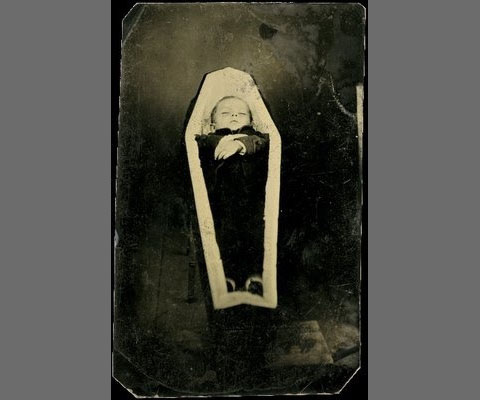

Several types of antique photographs, most often ambrotypes and tintypes, but sometimes even old prints on paper, are very commonly misidentified as daguerreotypes, especially if they are in the small, ornamented cases in which daguerreotypes made in the US and UK were usually housed. The name “daguerreotype” correctly refers only to one very specific image type and medium, the product of a process that was in wide use only from the early 1840s to the late 1850s.