The Diamond Sūtra is a Mahāyāna sūtra from the Prajñāpāramitā, or “Perfection of Wisdom” genre, and emphasizes the practice of non-abiding and non-attachment. The full Sanskrit title of this text is the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra.

The Diamond Sūtra is a Mahāyāna sūtra from the Prajñāpāramitā, or “Perfection of Wisdom” genre, and emphasizes the practice of non-abiding and non-attachment. The full Sanskrit title of this text is the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra.

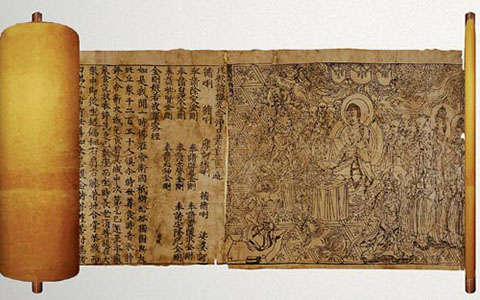

A copy of the Chinese version of Diamond Sūtra, found among the Dunhuang manuscripts in the early 20th century by Aurel Stein, was dated back to May 11, 868. It is, in the words of the British Library, “the earliest complete survival of a dated printed book.”

The full history of the text remains unknown, but Japanese scholars generally consider the Diamond Sūtra to be from a very early date in the development of Prajñāpāramitā literature. Some western scholars also believe that the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra was adapted from the earlier Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra. Early western scholarship on the Diamond Sūtra is summarized by Müller.

The first translation of the Diamond Sūtra into Chinese is thought to have been made in 401 CE by the venerated and prolific translator Kumārajīva. Kumārajīva’s translation style is distinctive, possessing a flowing smoothness that reflects his prioritization on conveying the meaning as opposed to precise literal rendering. The Kumārajīva translation has been particularly highly regarded over the centuries, and it is this version that appears on the 868 CE Dunhuang scroll. In addition to the Kumārajīva translation, a number of later translations exist. The Diamond Sūtra was again translated from Sanskrit into Chinese by Bodhiruci in 509 CE, Paramārtha in 558 CE, Xuanzang in 648 CE, and Yijing in 703 CE.

The Diamond Sūtra, like many Buddhist sūtras, begins with the phrase “Thus have I heard” (Skt. evaṃ mayā śrutam). In the sūtra, the Buddha has finished his daily walk with the monks to gather offerings of food, and he sits down to rest. Elder Subhūti comes forth and asks the Buddha a question. What follows is a dialogue regarding the nature of perception. The Buddha often uses paradoxical phrases such as, “What is called the highest teaching is not the highest teaching”. The Buddha is generally thought to be trying to help Subhūti unlearn his preconceived, limited notions of the nature of reality and enlightenment. Emphasizing that all forms, thoughts and conceptions are ultimately illusory, he teaches that true enlightenment cannot be grasped through them; they must be set aside. In his commentary on the Diamond Sūtra, Hsing Yun describes the four main points from the sūtra as giving without attachment to self, liberating beings without notions of self and other, living without attachment, and cultivating without attainment.

Throughout the teaching, the Buddha repeats that successful assimilation of even a four-line extract of it is of incalculable merit and can bring about enlightenment. One specific extract that draws much attention in this respect is a highly ornate four-line verse about impermanence appearing at the end of the sūtra. Section 26 also ends with a four-line gatha.

All composed things are like a dream,

a phantom, a drop of dew, a flash of lightning.

That is how to meditate on them,

that is how to observe them.

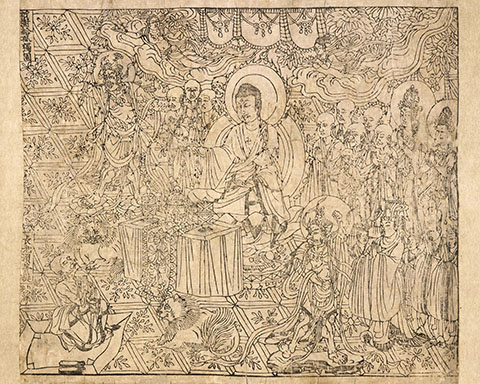

Here is a wood block printed copy in the British Library which, although not the earliest example of block printing, is the earliest example which bears an actual date. The book displays a great maturity of design and layout and speaks of a considerable ancestry for woodblock printing.

The extant copy has the form of a scroll, about 5 meters (16 ft) long. The archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein purchased it in 1907 in the walled-up Mogao Caves near Dunhuang in northwest China from a monk guarding the caves – known as the “Caves of the Thousand Buddhas”.

The colophon, at the inner end, reads:

Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 15th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong [11 May 868].

This is approximately 587 years before the Gutenberg Bible was first printed.

In 2010 UK writer and historian Frances Wood, head of the Chinese section at the British Library, was involved in the restoration of its copy of the book. The British Library website allows readers to view the Diamond Sutra in its entirety.