| Discourses | Biography | Portfolio |

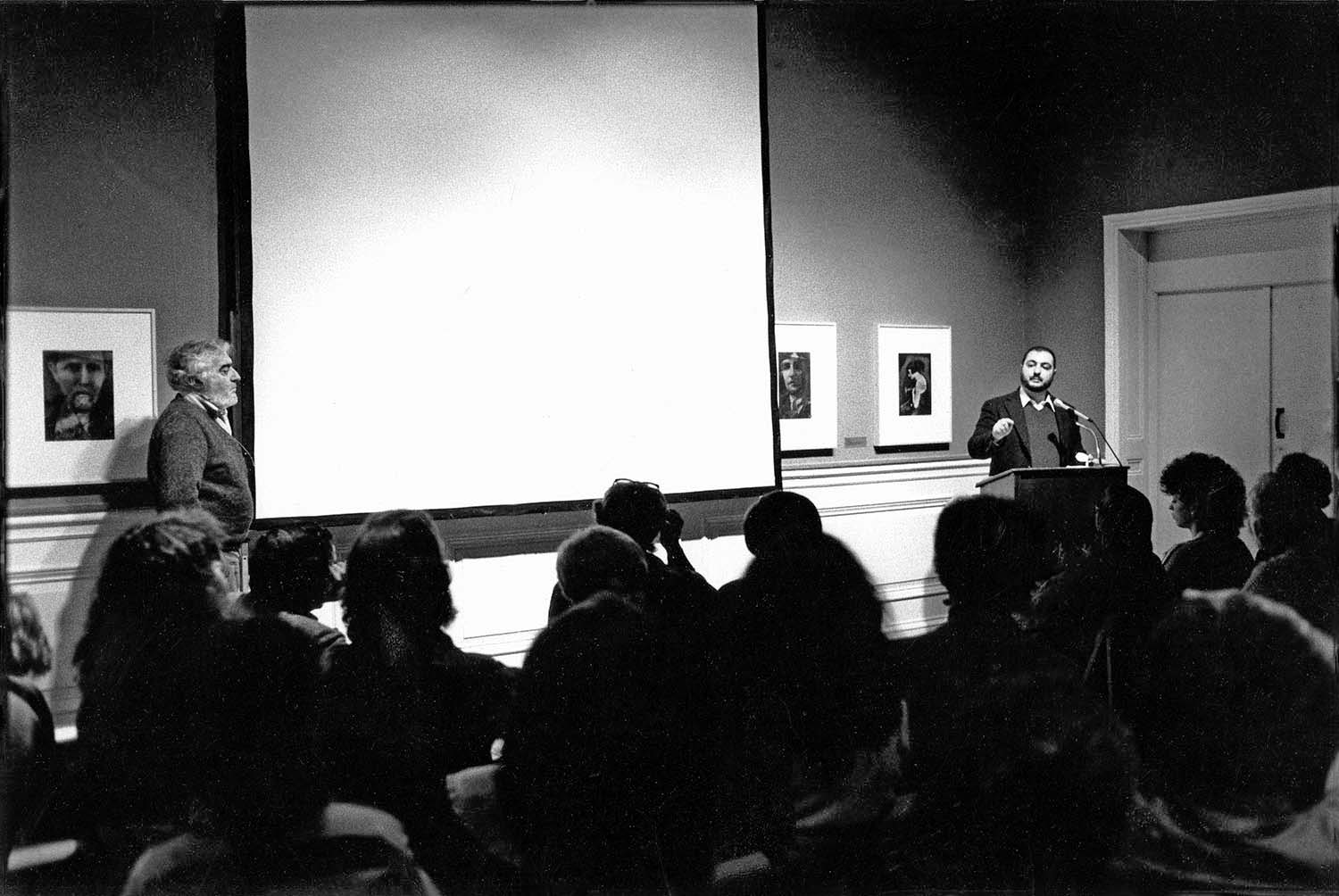

Cornell Kappa, founder of the International Center of Photography, introduces Abraham Menashe, March 2, 1983

ICP, 1130 Fifth Avenue, N. Y. City

The Healing Image

In the darkest recesses of the caves in Altimira, Spain, as well as those of Lascaux, France, we find awesome prehistoric paintings and frescoes: red bison, black horses, herds of earth colored oxen.

Surrounded with lines meant to represent spears, many of the creatures are portrayed as wounded and dying. It is evident that these images served a far more serious purpose than mere decoration. It is also widely recognized that these caves served as sanctuaries, and the paintings produced as part of a magical ritual to ensure a successful hunt.

For the men of the Old Stone Age, by making a likeness of an animal, they meant to bring the animal itself within their grasp, and in portraying it as wounded, they had killed the animal’s vital spirit. Those ancient frescoes are hauntingly beautiful and leave us with a sense of encounter with another world. They hold a special place in our lives because they symbolize man’s attempt at gaining dominion over the forces that affect his species.

Primitive pictures were not made by people who wanted to create art. They were made to entice the spirits and as offerings to the Gods. Because primitive man was at awe with his environment, the images produced possessed power. This reverence for life gave the image a rich and transporting beauty–a mystical depth rare in the annals of art. As language developed, the meaning of the image diminished. Today the image is subordinate to the word and used less as a vehicle for expressing man’s spiritual psyche and more as a means of documentation. We thus find ourselves constantly surrounded with photographic documentation, tracking man’s inhumanity to man. These images form our modern day mural.

As much as documentation is needed to preserve and explain our history, we are saturated with images of suffering. Because of photography’s instantaneous abilities, every passing hour adds to this mural a fresh moment of injustice, famine, and the makings of a new war. Our senses have been dulled, our hearts grown cold.

Life, no matter how generous, is a daily struggle. There is little around that truly provides comfort, yet it is a miracle how we manage to hold on. There must be another way to experience life besides being pulled through it kicking and screaming. It requires our willingness to change our goal.

We need to be exposed more often to images that affirm life. The 1955 exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art entitled The Family of Man, established a yet unequaled standard of achievement because it successfully mirrored Edward Steichen’s belief that photography should be an affirmation. That belief is the thread that elevates the artistic effort from banality, binds the cause of enduring artists, and reflects the true meaning of art. In his Personal Credo, first published in the 1944 Annual of Photography, and reread again on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Ansel Adams said, “I believe that man should build strength unto himself, affirming the enormous beauty of the world, and I believe in photography as one means of expressing this affirmation.”

To affirm is to validate our humanity, to say yes to our existence. This validation is the very breath of The Healing Image. The healing image delights in life’s richness, and is based on strength rather than weakness. It is a moment that renews, transforms, and unifies.

D. H. Laurence, in his essay Making Pictures, wrote “Art is a form of supremely delicate awareness and atonement…the state of being at one with the object.” To be at one with the object one must first be at peace with oneself. When the physical senses are hushed and we begin to listen to our inner voice, we notice that moments of true healing and growth occur. When we are healed, we see with innocence and through the eyes of lovers.

We have ample testimony that the artist tends to look upon his creation as a living thing. The life of the work created must give of itself and add to the texture of our lives, illuminating our way.

The healing image does not necessarily seek to change society or our conscience. It is autonomous in its grace and warmth. It is simply an object of contemplation, an icon which embodies the inner truth of things. It is, in Thomas Merton’s words, “the highest expression of praise and worship.” The artist creates it for the the sheer pleasure of communion. When finished, it cannot help but become an offering, a testament to life and goodness. It offers the artist and his/her audience redemption from a life of desperation.

Marc Chagall is the chief modern exponent of romantic love. His paintings seem naive because they exhibit an almost childlike belief in the power of love. He is not interested in shocking the viewer, he literally illustrates that love overcomes physical facts and mystically transports individuals despite the laws of gravity and aerodynamics. In Flying Over The Moon, a couple floats above a village as if in a fairy tale or dream.

The work of Vincent Van Gogh also adds to our appreciation of life’s vitality. His Starry Night animates the entire scene so that everything appears to be alive and in motion. This sense of aliveness of all things, characterizes Van Gogh’s work even when he paints a chair or shoes. All creation exhibits the divine presence.

The sculpture Henry Moore is yet another example of an artist who expresses spiritual affirmation and renewal. His UNESCO sculpture casts humanity in a monumental role. Monumental because Moore celebrates the durability of man. The massiveness of the figure creates a powerful sense of stability, and the large forms he has abstracted from the thighs and torso are akin to the shapes of the old hills and eroded mountains. The image of man here is Promethean, man suffers and is defiant.

Because mankind in the twentieth century have known two great wars and live with the knowledge of their possible extinction in a third, it is not surprising that art has expressed symptoms of fear and occasional feelings of hopelessness. Dorothea Langue, a photographer during the depression, wrote in 1952, “that the world is often unsatisfactory cannot be denied, but it is not for all that one we need abandon… Ours is a time of the machine, and ours is a need to know that the machine can be put to a creative effort. If it is not, the machine can destroy us. It is within the power of the photographer to help make the machine an agent more of good than of evil… and as artists undertake not only risks but responsibility. It is with responsibility that both the photographer and his machine are brought to their ultimate tests.”

In a rapidly chilling time we must somewhere find warmth or die. As St. Basil said of his own City, “the famine of love among us is terrible… charity of the many has grown cold.” It is a moral challenge and with deliberate choice that we must see through the window of love and see all things as we would have them be.

The notion of God is hard to discuss directly; yet, we can see His diverse faces through the deeds people do – through the love people share – through the beauty in the world. I’ve come to the point where I have committed myself to the exploration of that love through my photography. The way we see is the way we choose and the way we choose is the way we are free.

Every being has personal beasts to conquer, mine is to clear the shadow that shades the heart. To reflect the gift of life. Because life is short, because we are a fragile people, because we need warmth, I choose The Healing Image. Mother Teresa told me “If you photograph with love, that work becomes prayer.” Through the image, we too, like ancient man, can gain power over the forces that affect us. As photographers we must provide hope. Hope is a sustaining human gift.

| Discourses | Biography | Portfolio |