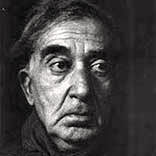

Constantine P. Cavafy, also known as Konstantin or Konstantinos Petrou Kavafis, or Kavaphes (April 29, 1863 – April 29, 1933) was a major Greek poet.

Constantine P. Cavafy, also known as Konstantin or Konstantinos Petrou Kavafis, or Kavaphes (April 29, 1863 – April 29, 1933) was a major Greek poet.

He worked as a journalist and civil servant. He has been called a skeptic and a neo-pagan. In his poetry he examines critically some aspects of Christianity, patriotism, and homosexuality, though he was not always comfortable with his role as a nonconformist. He published 154 poems; dozens more remained incomplete or in sketch form. His most important poetry was written after his fortieth birthday.

GRAN REFIUTO

Constantine P. Cavafy

For some people the day comes

when they have to declare the great Yes

or the Great No. It’s clear at once who has the Yes

ready within him; and saying,

he goes forward in honor and self-assurance.

He who refuses does not repent. Asked again,

he would still say no. Yet that no—the right no—

undermines him all his life.

=====

THE HORSES OF ACHILLES

Constantine P. Cavafy

When they saw Patroklos dead

—so brave and strong, so young—

the horses of Achilles began to weep;

their immortal nature was upset deeply

by this work of death they had to look at.

They reared their heads, tossed their long manes,

beat the ground with their hooves, and mourned

Patroklos, seeing him lifeless, destroyed,

now mere flesh only, his spirit gone,

defenseless, without breath,

turned back from life to the great Nothingness.

Zeus saw the tears of those immortal horses and felt sorry.

“At the wedding of Peleus,” he said,

“I should not have acted so thoughtlessly.

Better if we hadn’t given you as a gift,

my unhappy horses. What business did you have down there,

among pathetic human beings, the toys of fate.

You are free of death, you will not get old,

yet ephemeral disasters torment you.

Men have caught you up in their misery.”

But it was for the eternal disaster of death

that those two gallant horses shed their tears.

=====

ITHAKA

Constantine P. Cavafy

Constantine P. Cavafy

there was an enormous mirror, very old;

acquired at least eighty years ago.

A strikingly beautiful boy, a tailor’s assistant,

(on Sunday afternoons, an amateur athlete),

was standing with a package. He handed it

to one of the household, who then went back inside

to fetch a receipt. The tailor’s assistant

remained alone, and waited.

He drew near the mirror, and stood gazing at himself,

and straightening his tie. Five minutes later

they brought him the receipt. He took it and left.

But the ancient mirror, which had seen and seen again,

throughout its lifetime of so many years,

thousands of objects and faces—

but the ancient mirror now became elated,

inflated with pride, because it had received upon itself

perfect beauty, for a few minutes.