Toward the end of my year in Nepal, two of my friends and I—with nothing but our backpacks—boarded a crowded bus for the long, dusty overland trip to Lhasa, Tibet. We stayed for three months, traveling like nomads all around the country on the backs of trucks, staying in tents, and always aiming straight for the temples and monasteries.

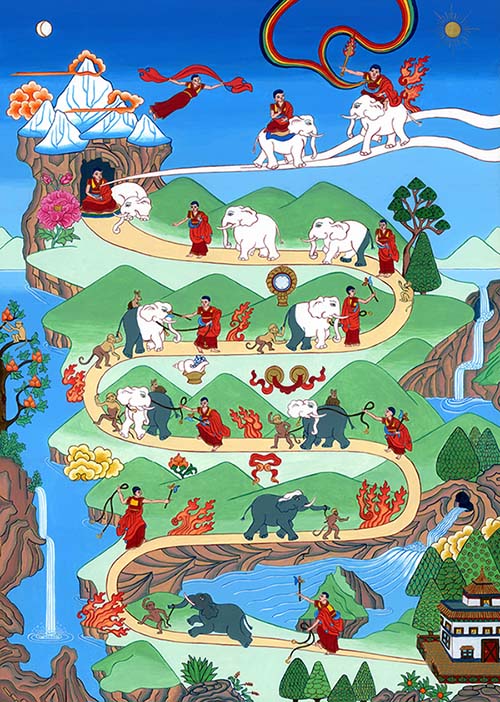

On the walls of the temples we visited, we came across a certain mural again and again. The mural, which was usually in the entryway, depicted a monkey and an elephant traveling uphill on a winding path. It seemed to be telling a story. Eventually I asked one of the temple keepers what it meant.

The temple keeper, a monk clothed in deep burgundy robes with a face beautifully etched with lines, replied that the mural was depicting the developmental process of meditation. The elephant, he explained, symbolized dullness. The monkey symbolized distraction.

“At the beginning of the path, the meditator’s mind is controlled by distraction and dullness, with distraction mostly in charge,” explained the temple keeper, pointing to the bottom of the mural where I noticed that the monkey was indeed leading the elephant by a rope.

“But by the end of the path, the monkey has fallen by the wayside. A monk has joined them and is riding the elephant, who has turned white, symbolizing that both dullness and distraction are tamed.

“The monk,” the temple keeper explained, “is mindfulness.”

Indeed, the image (below) showed the monk gradually disciplining the elephant and monkey with his stick and lasso. In the final scene, at the very top, the path becomes a rainbow upon which a white elephant strolls toward the heavens, with the monk sitting in meditation posture on the elephant’s back.

The image stays with me as a compelling depiction of the role of mindfulness on the path to tranquility. When we first start to meditate, the mind is all over the place. It is like the wild monkey, bouncing from one thought or idea to another. Or sometimes the mind is sleepy and lethargic like the slow elephant. It lacks the sharpness needed to pay attention in a sustained way. Neither state is conducive to concentration, clarity, or ease.

To tame our distracted, scattered attention, we turn it toward an object—the breath, for example. At first the mind will not stay focused for long. It bounces away, distracted by a thought or an idea. Or the mind sinks into torpor and forgets entirely what it was doing. What was it we were doing? Oh yes. Then we coax the mind back again to the breath. This happens over and over, a process called placement and replacement.

The faculty we use to bring the mind back is mindfulness—the monk with the stick. Every time the monk with the stick shows up, the muscle of attention is strengthened just a little bit. We learn to remember to stay on task, simply paying attention to the breath. As attention stays on its object longer and longer, the mind’s restlessness begins to calm down, resulting in a state known as shamatha (tranquility).

This is one way to tame the mind, a cognitive approach to mindfulness. Mental discipline is employed to harness and gather attention, to keep it focused on its object.

But there is an alternative and complementary approach to developing mindfulness. This model is the yogic model of mindfulness. In a yogic approach, attention emerges from deep within the body. In this system, the path to a mindful life is not paved by taming and subduing but rather by surrender. This is the approach that I am calling somatic mindfulness. Somatic mindfulness is the body’s mindfulness, a relaxed, loving attention spontaneously experiencing the present moment through the entire bodymind.

Like the monastic model, this model acknowledges and understands the mind’s distraction, scatteredness, and discursiveness as sources of suffering. But the solution to dealing with this wild mind is not to harness control of it, setting attention back again and again on an object of focus.

Somatic mindfulness is informed by one very simple observation: the mind is distracted, but the body is not. The body is not thinking or ruminating. It is just feeling and being, present, aware, and vibrant. In other words: the body is already mindful.

The turning point in this model that sets somatic mindfulness apart from the more orthodox model comes at the moment of distraction. At the moment of distraction, instead of prioritizing control, a practitioner of somatic mindfulness releases control and allows attention to be drawn back by the body (or by the feeling of breath, which is, after all, a somatic feeling).

Somatic sensation, such as the air in your nostrils or the rise of your diaphragm, re-centers attention. The return is experienced not as a discipline of effortful redirection by a higher executive function but as a natural draw to the body’s steady wakefulness, like iron filings returning to a magnet. Scattered attention represents the iron filings, and the body is the magnet.

When the mind relaxes its grip, the body leads the way. It’s a great relief for the mind, in fact.

Put another way, the model is not one of taming but trust. Perhaps the monk does show up, but the monk does not have a stick. The monk prostrates to and dissolves into the breath. The doorway into a sustained, relaxed attention is to let go of control and find refuge in the body’s immediate present sensory field. When the mind relaxes its grip on the process, the body models sustained attention. The body leads the way. It’s a great relief for the mind, in fact.

If you have been struggling to develop mindfulness, this may come as a surprise. The secret to stabilizing your practice has not only been right under your nose but it is your nose— and the rest of your body, too, for that matter.

If you are new to meditation, this might sound like a subtle difference, to allow attention to follow the body’s lead versus developing mental attention using the body. But it turns out to be an important distinction, especially when it comes to the inner experience of meditation practice over time. Here is a practice of somatic mindfulness that can help you begin to discover your body’s natural attention.

Practice: Surrendering to the Breath

Turn your attention to the breath. Notice its wavelike quality, how the breath rises like the swell of the ocean and then falls like the dip between swells.

Gradually explore the sensations that are unfolding as you breathe. Notice a fresh, alive feeling in your nostrils as you inhale. Notice the gentle warmth of the exhale. Notice the rise and fall of your diaphragm.

See if you can find a balance between paying attention and being relaxed, letting go of tension with every exhale.

At some point, after sitting for a while, you will become distracted and forget you have given yourself this task of focusing on the breath. Your attention will wander. You will become caught up in a train of thought.

Then there is the moment of noticing you are distracted. At that moment, do not make any effort to refocus on the breath. Instead, allow the breath itself to draw you back in. Let the natural sensations of breath moving within your body—the feeling of freshness in your nostrils, the rise and fall of your diaphragm, the expansion of your heart center—draw you back, like a magnet draws iron filings.

Surrender to the natural mindfulness of your body.

— © Tricycle magazine, Winter 2021, by Willa Blythe Baker