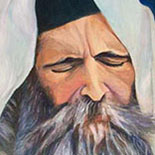

Nachman of Breslov (also known as Reb Nachman of Bratslav, Reb Nachman Breslover, Nachman from Uman (April 4, 1772 – October 16, 1810), was the founder of the Breslov Hasidic movement.

Nachman of Breslov (also known as Reb Nachman of Bratslav, Reb Nachman Breslover, Nachman from Uman (April 4, 1772 – October 16, 1810), was the founder of the Breslov Hasidic movement.

Rebbe Nachman, a great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, breathed new life into the Hasidic movement by combining the esoteric secrets of Judaism (the Kabbalah) with in-depth Torah scholarship. He attracted thousands of followers during his lifetime and his influence continues until today through many Hasidic movements such as Breslov Hasidism. Rebbe Nachman’s religious philosophy revolved around closeness to God and speaking to God in normal conversation “as you would with a best friend.” The concept of hitbodedut is central to his thinking.

In his short life, Rebbe Nachman achieved much acclaim as a teacher and spiritual leader, and is considered a seminal figure in the history of Hasidism. His contributions to Hasidic Judaism include the following:

- He rejected the idea of hereditary Hasidic dynasties, and taught that each Hasid must “search for the tzaddik (‘saintly/righteous person’)” for himself — and within himself. He believed that every Jew has the potential to become a tzaddik.

- He emphasized that a tzaddik should magnify the blessings on the community through his mitzvot. However, the tzaddik cannot “absolve” a Hasid of his sins, and the Hasid should pray only to God, not to the Rebbe. The purpose of confiding in another human being is to unburden the soul as part of the process of repentance and healing. (Modern psychology supports this idea, which is the “Fifth Step” in many 12-step programs for recovery.)

- In his early life, he stressed the practice of fasting and self-castigation as the most effective means of repentance. In later years, however, he abandoned these severe ascetisms because he felt they may lead to depression and sadness. He told his followers not to be “fanatics”. Rather, they should choose one personal mitzvah to be very strict about, and do the others with the normal amount of care.

- He encouraged his disciples to take every opportunity to increase holiness in themselves and their daily activities. For example, by marrying and living with one’s spouse according to Torah law, one elevates sexual intimacy to an act bespeaking honor and respect to the God-given powers of procreation. This in turn safeguards the sign of the covenant, the brit milah (“covenant of circumcision”) which is considered the symbol of the everlasting pact between God and the Jewish people.

- He urged everyone to seek out his own and others’ good points in order to approach life in a state of continual happiness. If one cannot find any “good points” in himself, let him search his deeds. If he finds that his deeds were driven by ulterior motives or improper thoughts, let him search for the positive aspects within them. And if he cannot find any good points, he should at least be happy that he is a Jew. This “good point” is God’s doing, not his.

- He placed great stress on living with faith, simplicity, and joy. He encouraged his followers to clap, sing and dance during or after their prayers, bringing them to a closer relationship with God.

- He emphasized the importance of intellectual learning and Torah scholarship. “You can originate Torah novellae, but do not change anything in the laws of the Shulchan Aruch!” he said. He and his disciples were thoroughly familiar with all the classic texts of Judaism, including the Talmud and its commentaries, Midrash, and Shulchan Aruch.

- He frequently recited extemporaneous prayers. He taught that his followers should spend an hour alone each day, talking aloud to God in his or her own words, as if “talking to a good friend.” This is in addition to the prayers in the siddur. Breslover Hasidim still follow this practice today, which is known as hitbodedut (literally, “to make oneself be in solitude”). Rebbe Nachman taught that the best place to do hitbodedut was in a field or forest, among the natural works of God’s creation.

- He emphasized importance of music for spiritual development and religious practice.